The Union government’s gross tax revenue has shown consistent growth over the years, with direct taxes outperforming indirect taxes in recent years. But a holistic view, combining both Union and state tax collections, presents a different story.

As per the total aggregate tax revenue, direct taxes account for less than 40 percent of India’s overall sum. In the FY2023 budget estimates, in fact, direct tax collection was estimated at 16.42 lakh crore, while indirect tax was estimated at 29.08 lakh crore, as per the RBI data, pointing to India’s reliance on indirect taxes.

Direct taxes, known for their equitable nature, impose a lesser burden on the economically disadvantaged compared to indirect taxes, which impact poor individuals and households more significantly.

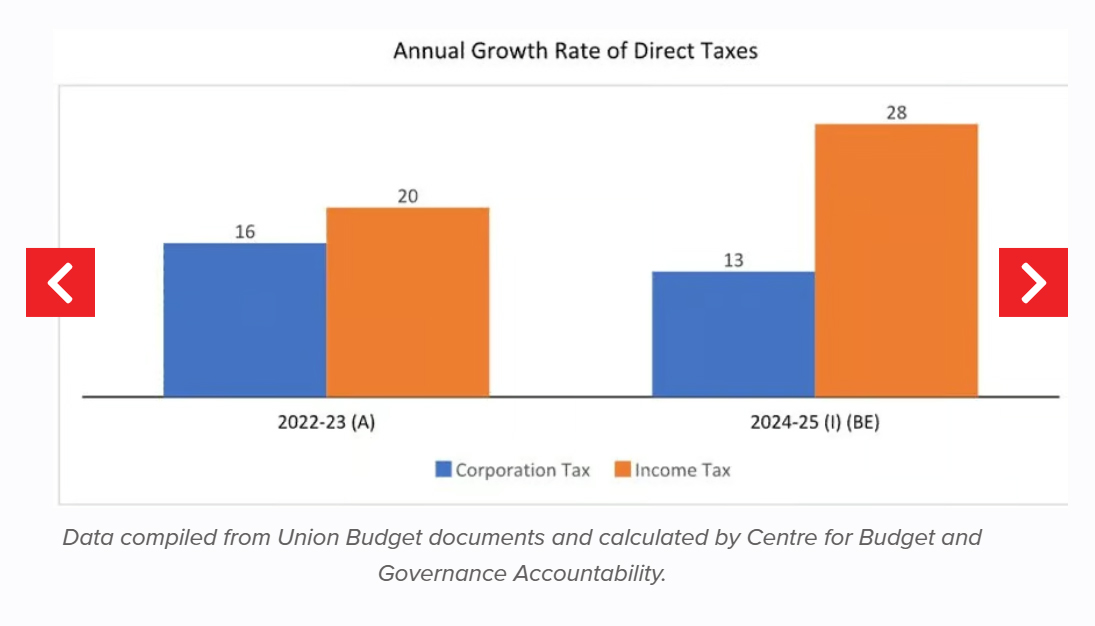

Even within the upward trajectory of direct tax collections by the centre, there has been a significant shift in its composition – between corporate and personal taxes. Since the fiscal year 2023, personal income tax’s contribution to direct tax revenue has recorded an increase.

The interim budget projections further indicated an increase of 28.4 percent in personal income tax in FY2025 from last year's estimates, which put it at 52.57 percent of gross direct taxes, while the growth in corporate tax is estimated at 13.02 percent.

While better compliance measures, adjustments in tax slabs, and technological innovations are driving the central government’s tax revenue through personal taxes, the growth of corporate income tax has been sluggish. This is despite the significant reduction in corporate tax rates in 2019.

The revenue from corporate income tax has not only fallen behind the nominal GDP growth rate but is also showing a decrease in buoyancy. This indicates that the increase in corporate taxes has been outpaced by economic growth, underscoring a concerning trend in tax revenue dynamics.

But what’s working out for the governments and what’s not? Let’s take a look.

GST as primary driver of Indirect tax collection

Despite initial hurdles in design and implementation, exacerbated by the impact of Covid-19 pandemic, GST has emerged as the primary driver of tax collection within indirect tax sources.

While the initial hiccups meant that GST revenue generation did not meet projections from FY2019 to FY2021, the end of the pandemic phase saw a resurgence in business activities, significantly boosting GST collections beyond pre-pandemic figures.

Notably, FY2022 emerged as a pivotal year for GST revenues, with CGST revenues surpassing budget estimates, a trend that continued in FY2023.

The Controller General of Accounts reported a 13.25 percent increase in CGST collection up to December 2023 as compared to the previous year. Despite the promising trend observed in the first three quarters of FY2024, suggesting a potential further improvement, the revised estimates are still kept in line with the initial budget estimates, reflecting a cautious approach towards revenue forecasting. This approach, despite the recovery, suggests an underlying concern about potential underreporting.

Trend of centralisation of taxes

With the increase in tax revenue, the Union government seems to have observed the trend of centralisation of taxes. In the interim budget, the share of the centre’s non-shared tax revenue declined from last year’s estimate, but still stood at the higher end at 14.1 percent.

The constitution permits the central government to levy certain cesses and surcharges for specific purposes, which have traditionally been imposed on a temporary basis. But recently many of these taxes have transformed into more permanent elements of the tax architecture. This has increased the centre's net tax pool, particularly because these revenues are not included in the divisible tax pool shared with the states.

These cesses and surcharges, including those for road and infrastructure on fuel sales, and for health and education, and the ones aimed at directly supporting specific sectors, can be levied under the exclusive powers wielded by the central government.

Over time, these levies have evolved into primary financing sources for the centre. But as state governments do not benefit from these additional taxes, it diminishes their potential for revenue growth. And the increasing accrual of cesses and surcharges also significantly impacts the spirit of cooperative federalism.

It must be noted that a government’s spending is defined by the size of its revenue kitty, making revenue mobilisation integral to the budget-making process for both the states and the centre. And tax revenue, comprising the proceeds from direct and indirect taxes, forms a major component of the government’s revenue sources, besides non-tax revenue.

For instance, for the flagship, centrally-sponsored schemes such as the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan and Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman or PM-POSHAN, nearly 99.9 percent of their budgets will be financed through education cess in FY2025.

The current tax dynamics underlines the need to focus more on widening the tax base through employment creation, and initiating measures to ensure tax compliance from the corporate sector. This will enhance the contribution of direct tax in the aggregate tax collection. The government can also employ further measures to simplify the GST collection process to ensure increased tax compliance and augmented revenue mobilisation.

More importantly, expectation from the Sixteenth Finance Commission would be to introduce measures to bring cesses and surcharges under the divisible tax pool, which is a long standing demand of the state governments.

12 February 2024

12 February 2024